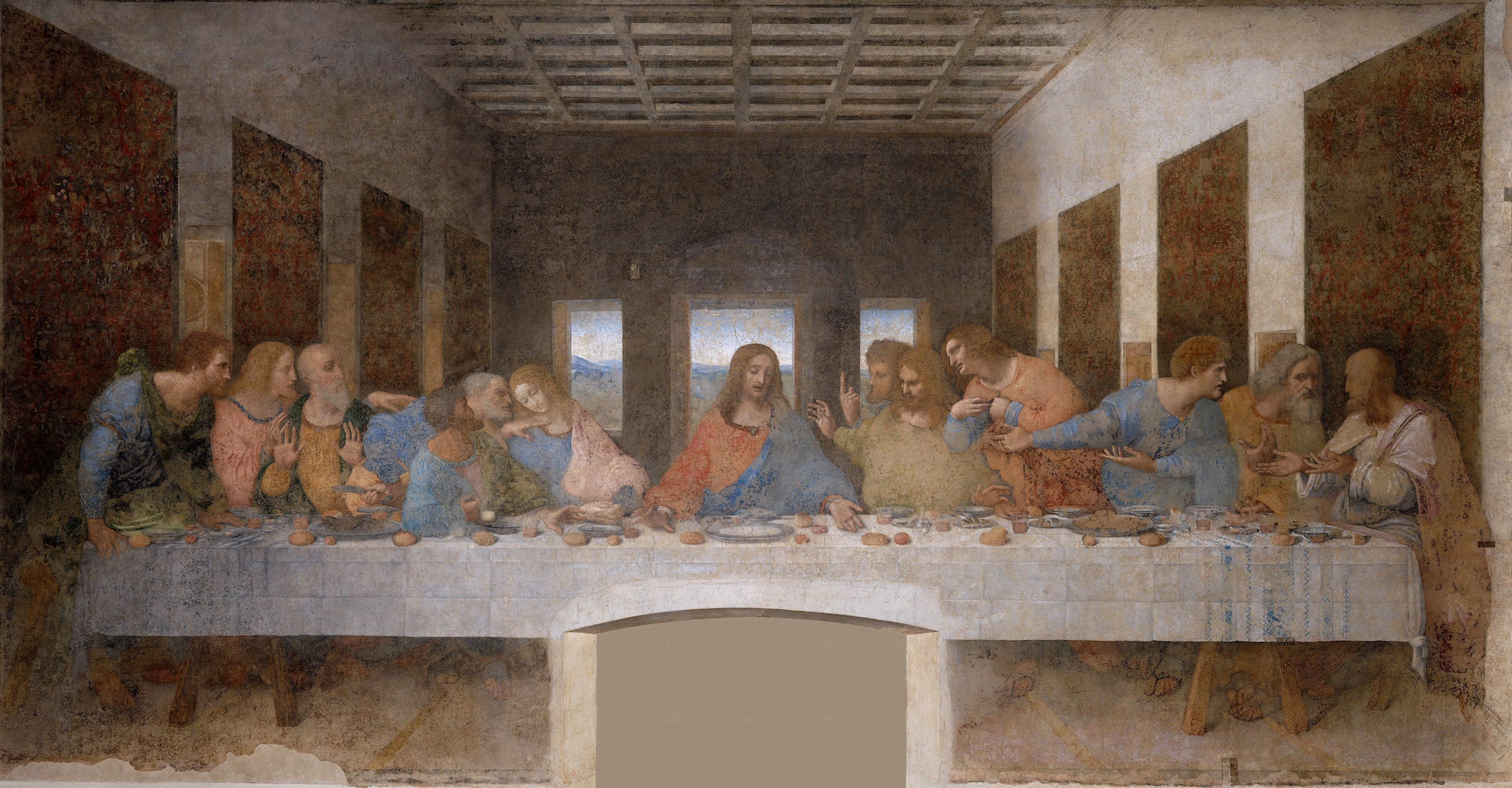

Most visitors to Milan will make the pilgrimage to see Leonard da Vinci’s Last Supper in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. This massive painting covered the back wall of the dining hall, inspiring silent reflection among the inhabitants. Most people are also familiar with the subject: the moment at the Last Supper when Jesus announces that one of those present will betray him.

However, there are other aspects to this painting that may well surprise you.

1. The Last Supper is not a fresco: it’s a mural using a technique known as fresco secco. Unlike normal fresco, where painters work on wet plaster so that the pigments become part of the wall, fresco secco mixes pigments with a binding agent, which is applied to a dry wall. The colours are bolder and brighter but, unfortunately, less durable. Within twenty years of its completion the Last Supper began to flake and had almost entirely disappeared a hundred years later.

2. The painting has survived many different violations. In 1625 the monks, believing the painting to be of no further value, cut a doorway through the painting, destroying Jesus feet and part of the table.

– In 1796, Napoleon’s troops used the space as a stable and amused themselves by throwing clay at the Apostles’ faces.

– In 1800 the building was flooded and the painting covered with green mould.

– Many of the seven documented attempts to restore the painting did more harm than good. In the 19th century restorers, using alcohol and cotton swabs, removed an entire layer of paint.

– In 1943 Allied bombers destroyed the entire monastery. Despite sandbagging, the painting still suffered damage.

3. The most recent restoration was completed in 1999, a 22 year, 50,000 hour project. The project was controversial, with criticism of the type water colour paint and the intensity of colour used. It is estimated that some seventeen per cent of the surface has been completely lost and that less than half of the surface currently visible was actually painted by Da Vinci.

4. This painting continues to excite the imagination with speculation about the recurrence of the number three; the meaning of the spilled salt in front of Judas and the leavened bread; the theory that Da Vinci himself is represented in the figure of St James the Lesser (second Apostle from the left).[/vc_column_text]

[/vc_column][/vc_row]

And if you’re interested in more, thriller writer Dan Browne has gone to town with all kinds of mysterious and mystical references in his book The Da Vinci Code.

To visit The Last Supper, you’ll need to book online some months in advance. The convent admits only small groups of about twenty people, for about twenty minutes at a time. Book at the official website to avoid the many scalpers and resellers and their ridiculous fees.

We always visit the Last Supper as part of our Milan and the Italian Lakes tour, next scheduled for June 2017.